The Delhi Sultanate, a significant chapter in medieval Indian history, was a dynasty-based Islamic empire headquartered in Delhi, flourishing from 1206 to 1526. This empire saw the succession of five influential dynasties: Mamluk, Khalji, Tughlaq, Sayyid, and Lodi, marking the beginning of Muslim rule in India and laying foundational aspects for the Delhi Sultanate history.

The establishment by Qutb al-Din Aibak, originally a slave-general of the Ghurid Empire, signified the start of a new era stretching until the precipice of the Mughal Empire’s rise. This period underscores the Delhi Sultanate’s crucial role in shaping the subcontinent’s socio-political and cultural landscape, to be further examined in terms of administration, governance, and architectural achievements.

Rise and Expansion of the Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate, established in 1206 by the Mamluk Dynasty, marked the beginning of a significant era in Indian history. The Mamluk dynasty, of Turkic Cuman-Kipchak origin, was the first of several dynasties to rule the region, setting a precedent for the expansion and governance of the sultanate.

Under the leadership of Qutb al-Din Aibak, the construction of iconic structures such as the Qutub Minar began, although it was completed by his successor, Iltutmish, who also made Delhi the permanent capital. This period was characterized by the consolidation of power and the stabilization of the empire’s boundaries.

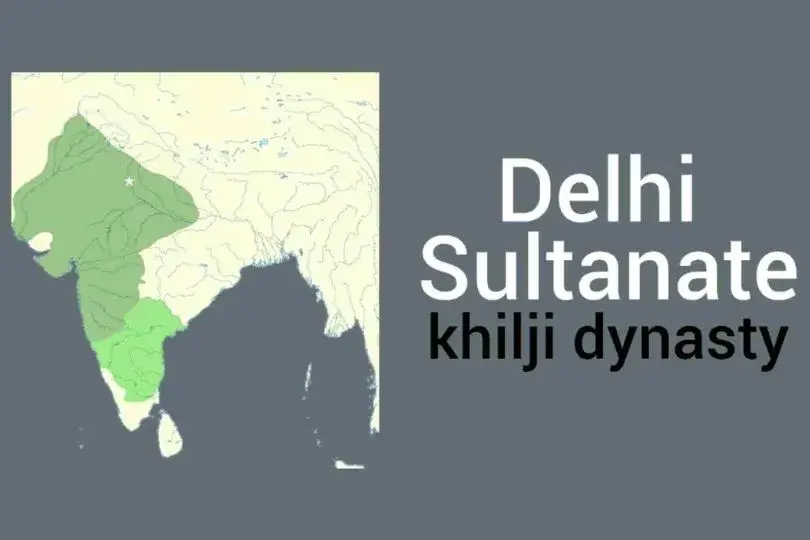

The Sultanate’s territorial reach peaked during the Tughluq dynasty, under Muhammad bin Tughluq, expanding to cover most of the Indian subcontinent. This expansion was not only a demonstration of military might but also of administrative acumen, as the empire managed to repel several invasions by the Mongol Empire, thereby preventing potential devastation.

Economic policies during this era also saw a shift, with the sultanate taking a more active role in the economy, which was a departure from the practices of previous Hindu dynasties. This included imposing stricter penalties on private businesses that violated government regulations.

Military strategies were pivotal to the Delhi Sultanate’s expansion. The army, initially composed of Turkic Mamluk military slaves, evolved into a more structured force with the addition of the Turco-Afghani regular units named Wajih, which played a crucial role in the sultanate’s military campaigns.

The Khalji and Tughluq dynasties further expanded the sultanate’s territory through extensive military campaigns. Alauddin Khalji, for instance, extended the empire southward into the Deccan, while the Tughluq dynasty’s campaigns aimed at consolidating control over the garrison towns in the hinterlands.

Despite these expansions, the sultanate’s control was often limited to fortified towns and military garrisons, with little sway over the surrounding rural areas. The Sultans primarily relied on trade, tribute, or plunder for resources, as direct control over agricultural lands was minimal.

The period of expansion under the Delhi Sultanate laid the groundwork for what would become a complex and multifaceted legacy, influencing the subsequent rise of other empires, including the Mughal Empire.

Administration and Governance

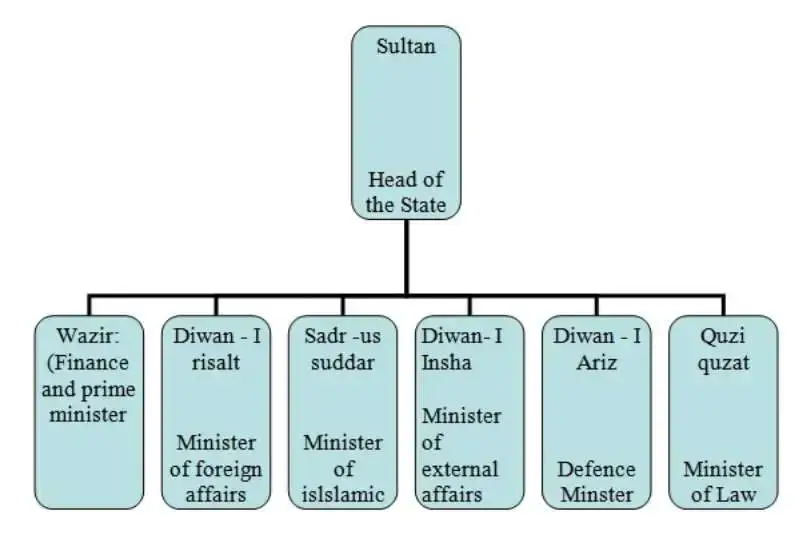

The Delhi Sultanate significantly enhanced its administrative framework, establishing a centralized system that profoundly influenced governance in the region. The Sultan held the highest authority, overseeing legal, military, and political domains, although succession issues often led to internal conflicts. Central administration was meticulously organized into various departments:

- Diwan-i-Wizarat (Finance Department): Headed by the Wazir or Vizier, this department managed the empire’s finances.

- Diwan-i-Ariz (Military Department): Commanded by the Ariz-i-Mumalik, it was responsible for military affairs.

- Diwan-i-Risalat (Religious Affairs): This department handled religious matters and pious foundations.

- Diwan-i-Insha (Correspondence Department): Managed the Sultanate’s communication and official correspondence.

Provincially, the land was divided into Iqtas, governed by Muqtis or Walis who ensured law and order and managed revenue collection. Each province was further divided into smaller districts known as Shiqs, overseen by Shiqdars.

At the local level, the village represented the smallest administrative unit, managed by village functionaries like Khut, Muqaddam, and Patwari. Larger administrative divisions, Parganas, comprised several villages, each managed by authorities such as Chaudhary, Amil, and Karkun.

The judicial system was dual, with Sharia law for Muslims and Hindu personal law for Hindus. The Chief Qazi, who also served as Chief Sadr, was at the helm, administering justice and managing religious endowments.

Revenue collection was diversified into five main types according to Shariyat, including Uchar, Kharaj, Jazia, Jakaq, and Khamas, which were pivotal in maintaining the state’s economy.

This robust and layered administrative system played a crucial role in maintaining the Delhi Sultanate’s governance and helped in the systematic management of its vast territories.

Cultural and Architectural Contributions

The Delhi Sultanate’s era was marked by significant cultural and architectural achievements that profoundly influenced the Indian subcontinent. The construction of iconic structures like the Qutub Minar and the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque highlights the architectural patronage of the period.

These monuments, along with others such as the Firoz Shah Kotla, were not only feats of engineering but also symbols of the Sultanate’s power and religious commitment.

Key Architectural Contributions

- Qutub Minar: Initiated by Qutb-ud-din Aibak, this minaret stands as a testament to the architectural ingenuity of the era, featuring detailed carvings and inscriptions.

- Tughlaqabad Fort: Built by Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq, this massive structure is known for its robust walls and extensive underground tunnel system, showcasing the military architecture of the time.

- Lodhi Gardens: Home to several tombs and monuments from the Sultanate period, it displays exquisite Islamic architecture.

The Sultanate was instrumental in the development of a new Indo-Islamic architectural style, characterized by a fusion of Islamic and Hindu elements, largely due to the collaboration between Hindu craftsmen and Muslim architects. This period also saw the emergence of the Hindustani language, a blend of modern-day Hindi and Urdu, which was significantly influenced by Persian culture introduced by Turkic and Afghan rulers.

Cultural advancements were equally noteworthy. The court of the Delhi Sultanate was a vibrant hub for scholars, poets, and artists from diverse backgrounds, contributing to a rich tapestry of intellectual and artistic life. Amir Khusro, a notable figure of this era, used Hindavi in his poetry, enriching the literary landscape of the time.

Moreover, the era’s influence extended beyond its time, setting a foundation for subsequent architectural styles in India, including those of the Mughal Empire. The Delhi Sultanate’s legacy in art and architecture remains a critical area of study in various academic fields, including the UPSC exams, underscoring its enduring impact on Indian history.

Decline and Legacy

The decline of the Delhi Sultanate was a multifaceted process influenced by a combination of political, social, religious, and economic factors. Politically, the autocratic rule, coupled with rulers’ lack of proper education and administrative skills, contributed significantly to the instability. The army was unorganized, and the feudal system further weakened the central authority.

Socially, the policy of religious intolerance fostered deep divisions within the society, exacerbating casteism and diminishing social cohesion. The theocratic state nature of the government, influenced heavily by the Ulema and orthodox Muslims, also played a crucial role in the religious turmoil that led to the sultanate’s decline.

Economically, the sultanate suffered from a lack of a solid financial foundation, with the royal treasury depleted through the amassing of wealth by the elite and not reinvested into the state. This economic instability made it difficult to sustain the military and administrative structures necessary for a vast empire.

The final blows came with Timur’s invasion in 1398, which drained the sultanate’s remaining wealth and significantly diminished its power and prestige. By 1388, succession disputes and palace intrigues had already set the stage for the inevitable decline. During the 15th and early 16th centuries, the absence of a paramount power led to constant wars and a general lack of direction in people’s lives.

The Delhi Sultanate’s treatment of Hindus, Buddhists, and other dharmic faiths was generally unfavorable, contributing to the legacy of division it left behind. Despite its decline, the Delhi Sultanate set the stage for the rise of several regional sultanates like the Bengal Sultanate, Bahmani Sultanate, and ultimately, the Mughal Empire. Its impact on making India more multicultural and cosmopolitan, and its role in introducing more mechanical technology in the Indian subcontinent, are notable aspects of its legacy.